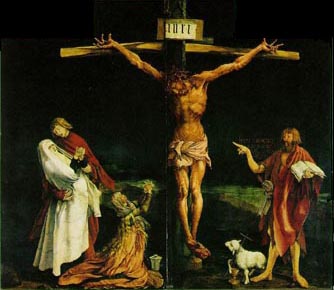

"Witnessing means pointing in a specific direction beyond the self and on to another. Witnessing is thus service to this other in which the witness vouches for the truth of the other, the service which consists in referring to this other...Standing in this service, the biblical witnesses point beyond themselves...One might recall John the Baptist in Grunewald's Crucifixion, especially his prodigious index finger. Could anyone point away from himself more impressively and completely ('he must increase, but I must decrease')...This is what the Fourth Evangelist wanted to say about this John, and therefore about another John, and therefore quite unmistakably about every 'John.'" Karl Barth, CD I.1.4.3, 109-110 [112].

So much to say about this painting--but we are only following one path here, the path to which Barth points us, the path of pointing away. Follow the prodigious finger.

To go ahead and say it: the phallic finger. Prodigious--extraordinary in size, abnormal, a miracle perhaps. Or a monstrosity. Perhaps all--that prodigious finger is not an end in itself. What it is--abnormal, excessive, monster, miracle--comes not from within, but from without. From where it points. Or, to whom. But Barth is right: it is a prodigious finger/phallus.

The object of desire, the one to whom the finger points: the monstrosity of (as) Christ. The prodigy, prodigium, Latin for monster. Or omen. Christ, the prodigy, the monstrous omen. "The prodigy is not only prewarning, but activation of the calamity at hand" (__Greek and Indo-European Etymology in Action: Proto-Indo-European *aǵ-__, Raimo Anttila, 114). The prodigious finger pointing away, pointing to the prodigy, the calamity at hand, the death of Christ.

Here we enter into the undoing. The phallic finger does not inscribe itself. It is not the goal, or object of attention. It exists in the painting as a sign, as a witness, as something to move past. It is magnified, enlarged, made prodigious so as to draw attention to its shrinking. Above the finger, it is written: he must increase but I must decrease. Enlarged, to draw attention to its shrinking. To his shrinking. To he shrinking.

Let us turn from shrinking and look at the large--and grotesque--feet of Christ. With the nail through the center, and blood dripping off the individual toes. The feet must have died first. They look ashen; even more than the rest of the dead, diseased, broken, bloody body. (I remember stories, in the Bible, about covering feet, and laying at the feet, and recall: a euphemism). Prodigious, dead feet.

Jesus' hands are also unusual. His fingers point--not to another person in the painting, but to the one absent, God, above. If there were time--I'm trying not to ramble...--we could examine those hands. One other person imitates those splayed fingers--Mary Magdalene, the smallest figure in the painting. Also, the only other one (besides Jesus) who isn't standing on her feet. The prodigious finger, pointing away from itself, towards the one with opened, uncontrolled, grasping hands. And thoroughly dead feet. (He came in the likeness of sinful flesh...).

"Writing is a passageway, the entrance, the exit, the dwelling place of the other in me--the other that I am and am not, that I don't know how to be, but that I feel passing, that makes me live--that tears me apart, disturbs me, changes me, who?--a feminine one, a masculine one, some?--several, some unknown, which is indeed what gives me the desire to know and from which all life soars. This peopling gives neither rest nor security, always disturbs the relationship to "reality," produces an uncertainty that gets in the way of the subject's socialization. It is distressing, it wears you out; and for men, this permeability, this nonexclusion is a threat, something intolerable" (Cixous, Sorties, in __The Newly Born Woman__, 86).

The permeability, the vulnerability, speaks of the end of self-mastery. Christ is the end of self-mastery. The death of human autonomy (self-government); the shriveling up of the enlarged...feet. For men, this is a threat. He must increase, I must decrease. The object of desire--the one to whom John's prodigious finger points--the crucified Christ. The death of the "phallogocentric" economy. Desired. Desirable. Lovely and teeming with life.

Cixous emphasizes writing; she performs a new writing, one not intoxicated by the desire to contain, conquer, control. Free from self-mastery, which involves (by necessity) an opposition to others: I, not you, am master. Beyond mastery, a different space, another way to write, another way to live, another way to relate. She thinks she's merely dreaming.

"Without the ambivalence, the liability to misunderstanding and the vulnerability with which [preaching] takes place, with which it is itself one event among many others, it could not be real proclamation" (Barth, 91 [94]). God speaks--the event of God's Word occurs--not in spite of, but through the weakness of our proclamation. To be a witness is to be weak. To be a witness is to have one's whole life amount to the task of pointing away, of highlighting not the self, but another. Not any other, either. But the Wholly Other--the Weakest Other, God in flesh.

Barth sometimes downplay the importance of the human form, the style of the presentation ("dogmatics does not seek to give a positive, stimulating and edifying presentation," p. 80 [82]). But he fundamentally recognizes its importance. The form does not guarantee that God speaks. God speaks always out of God's freedom. Nevertheless, one can point to Christ in a way that actually points to oneself (the kingdom of the Selfsame, in Cixous' terms). One can witness to one's strength; which means one can point away from Christ, and thus, even in the form of witnessing, one can fail to witness at all. The form matters. The way we write matters. It displays who we think we are, and, by God's grace, the one to whom we point.

To write in a way that embraces the dead, prodigious, monstrous, saving omen of Christ. And his dead feet. A challenge. Joyful, exhilarating, and terrifying. "For men, this permeability, this nonexclusion is a threat." The threat of losing control. "She lets the other tongue of a thousand tongues speak--the tongue, sound without barrier or death" (Sorties, 88). A beautiful picture of the feast we celebrated two weeks ago--Pentecost. Life beyond the dead feet. Come, Holy Spirit.