Monday, August 10, 2009

The Irresponsibility of Christian Missions

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Natural Theology and Colonial Missions

In Savage Systems, Chidester highlights a peculiar feature of colonial comparative religion: when the colonial boundary (the "frontier") is being contested by an indigenous population, the people are deemed to have no religion. However, "when the frontier closes, and hegemony has been established, a dominated subjected people are discovered to have a religion that can be inventoried and analyzed" (69). For example, the Hottentots lacked a religion from 1600-1654, then had one once a European settlement was established. When this establishment expanded, the Hottentots were again deemed areligious (from 1685-1700). Once the expansion ceased and the settlement was stablilized, the Hottentots were seen to possess a native religion. However, the colony started to spread again in 1770 and thus the Hottentots were again deemed to lack any religion (69). Even when they were deemed to have a religion, it was a religion that either resembled the stubbornness of the Jews or the superstition of the Catholics (70): "the Hottentots were credited with a religion that discredited them" (70).

The difference between Jews and Catholics seems to be based on a different failure. Jews stubbornly resisted Christian conversion, and thus exhibit a moral failure that explains their nonconversion; Catholic superstition is a sign of ignorance. Thus, the Hottentots' resistance to Christian conversion stemmed from either a moral or an intellectual failure. The intellectual failure was ultimately traced back to a different kind of moral failure, laziness. All three features could be tied together; Georg Meistert claimed in 1687 that the "absence of any religion among them was equivalent to their lack of literacy and industry" (45). Given their "bestial" language (37), the Hottentots necessarily lacked the ability to produce any kind of natural religion (and therefore, any proper human society, and therefore, any proper humanity per se).

Even though the recognition or denial of Hottentot religion constantly shifted, the missionaries zeal to analyze and discover (or produce) the native religion remained constant. Whether the verdict was positive or negative, the question was always being posed (and not only by missionaries but also by travelers, explorers, scientiests, and colonial administrators). No observer thought that the Hottentot's would exhibit the marks of "revealed religion," but they all pondered whether they were capable of producing a natural religion.

Natural theology, in the broadest sense of the term (especially as it is developed on the mission field in colonial Southern Africa), is the search for a merely natural (meaning, non-divinely inspired, not revealed) religiosity. What the European observers tried to catalogue was whether Hottentots had any idea of God, a transendent creator, and whether they developed any kind of rituals and ethics to relate to that idea. They knew that the Hottentots had various customs and rituals; the question was whether these rituals marked the presence of a rudementary knowledge of God or whether they marked mere superstition (and hence ignorance, laziness, and the absence of religion).

Chidester catalogues how the answer to this question varied according to the solidity of colonial control. In short, fighting natives had no religion (and hence were subhuman); conquered natives were religious after all (and hence capable of being absorbed into civilization). What interests me is how this compartive procedure stems from the search for a "point of contact" within the indiginous culture that would prepare it for the gospel. If the people resist the gospel, then they either lack a cultural starting point altogether (which makes them less than fully human), or they exhibit a cultural moral failing that prevents the gospel from taking root (laziness or stubbornness).

The search for a point of contact thus brings with it a compartive procedure. The missionary's native culture--a culture that has accepted the gospel--bears the marks of proper human culture. It has proven to be receptive to the gospel, and therefore (either naturally or by grace), has been brought out of sinful resistance. Those who refuse the gospel fail to measure up to the proper form of human receptivity (modelled by the missionary's culture). They lack what the sending community possesses: industry, civilization, intelligence, language, literacy, piety, a proper understanding of authority, etc. The resistant native population, within this strategy of comparison, can only be registered as a lack, as an absence, as the inverted image of the (colonial) missionary. They therefore lack religion. The dominated population is no longer violently opposed to the colonial settlement; they therefore exhibit some kind of potential harmonization within European conquest. They have some unformed religious potential.

This comparative natural theology held a privileged place within colonial missions. Missionaries (and other European observers) continually searched for--and registered (or produced) the presence or absence of--an African "unknown God." Convinced that there ought to be a "point of contact" (an African natural religion), European missionaries expressed shock at how uncivilized (and bestial) the areligious African were. Once they were brought under colonial control, their continual resistance to the gospel was read as a deformed religious response (on model with the Jews and Catholics). Natural theology, therefore, operated as a kind of intellectual backdrop (already worked out in missional polemics with Muslims, Jews, and later Catholics) through which to register the human differences encountered in the colonial world. The debate surrounding natural theology (i.e. Karl Barth's strident rejection of it) ought to be placed within this context. Natural theology is not just a doctrine but a disposition, a way of inhabiting the world that carries with it certain procedures of comparison and judgment whose concrete force can be most properly felt on the colonial mission field. In other words, the practical outworkings of natural theology are what Chidester describes in, and calls, "Savage Systems."

Thursday, July 23, 2009

The Secularity of the Word (Barth, Summary of I/1, §5)

Invariably, then, faith is acknowledgment of our limit and acknowledgment of the mystery of God’s word, acknowledgment of the fact that our hearing is bound to God himself, who now leads us through form to content and now from content back to form, and either way to Himself, not giving Himself in either case into our hands but keeping us in his hands.

Karl Barth, I/1, p. 176.

After discussing the form of the Word of God (§4), Barth examines the nature of the Word of God (§5). In this section, Barth works out how the Word is spoken to the creature without becoming the creature’s possession. The Word spoken to the creature is Jesus Christ (153), God with us, and hence the what is actually a who, and as a divine who can never be equated or placed under the control of the creature. Accordingly, Barth shifts the emphasis from the what to the how: if God’s Word--which cannot be “anticipated or repeated” (132)--is spoken to us in three forms, how is it spoken to us?

To answer the question how, Barth invokes the distinction between form and content. The Word (content) is given to us (unveiled) but in a hidden (veiled) way (form). The content (the Divine Word) is never accessible apart from the form it takes as a free address to specific, sinful creatures. The form, for its part, only bears the content by virtue of the divine freedom and grace: whether the form truly is the Word of God depends solely on God’s free choice.

God speaks concretely, and since it is God who speaks, God’s Word is productive: God’s Word claims fallen humanity for Godself, and in so doing, creates a new situation and a new being (one who is summoned to respond to God’s claim). God’s Word precedes, and hence does not depend, on the human response: “the Church is the Church as it believes and proclaims that prior to all secular developments and prior to all its own work the decisive word has in fact been spoken already regarding both itself and also the world” (155). Mission can only precede on the assumption that “the heathen” is “already drawn into Christ’s sphere of power” (153).

If the form can never guarantee the content, then we can never speak about the how of God’s Word except in response to God’s actually spoken Word (164). Since God’s Word never comes at us directly, but indirectly--in the garment of fallen, creaturely reality--all “we think and say about its how has its substance not in itself but outside itself in the Word of God, so that what we think and say about this now can never become the secret system of a what” (164). The indirectness of God’s Word can never be dissolved; it never becomes clear (and hence possessed): “the veil is thick. We do not have the Word of God otherwise than in the mystery of its secularity” (165). The form of God’s Word is an “unsuitable medium for God’s self-presentation” (166). Unsuitable, but not impossible. The form veils the unveiling: “He will not and cannot unveil Himself except by veiling Himself” (165, emphasis added). The veiling is necessary, not for God, but for us. “If God did not speak to us in secular form, He would not speak to us at all” (168). Christ enters into our world, the world of estranged creatures, the secular world. Therefore, “to evade the secularity of His Word is to evade Christ” (168).

One cannot peer behind the form--the garment of fallen creation--to get hold of the content (divine Word). Humans never have a direct hold on God. The Church is not “outside with God” while the world “is inside without God” (155). Barth offers two arguments against this church-world distinction. First, the Word of God is spoken to the whole “world of man standing over against the Word of God” (155). Therefore, “the world cannot be held to its ungodliness by the Church” because Christ has already spoken to--claimed--this ungodly world (155). Secondly, due to the distinction between form and content, we can never guarantee that our own words actually convey the Word of God. Considered “in and of itself our thinking is irrefutably non-christian” (176). To place the Church outside of or over against the world necessitates placing our faith in the propriety of our own speech (our “Christian grammar”). However, our faith rests not in our thoughts--the form--but in the one who has pledged to be with sinful humanity, i.e., God’s Word, Jesus Christ. The “real interpretation of its form can only be that which God’s Word gives itself” (167). We can never interpret the form ourselves but always depend on God’s Word to interpret itself. The church, therefore, can never interpret its own form, and thus can never set itself over against the world. The Church knows itself only in faith, that is, in God’s Word, which it can never possess but on which it always and constantly depends.

Barth’s use of the form/content distinction actually undermines the coherence of that distinction. Ordinarily, we think of the form/content binary along the lines of the split between sign/signified: what is present to us (form/sign) provides what is absent (content/signified). Instead of providing a deconstructive analysis of the endless deferrals within language (différance), Barth fundamentally places language--at least the language of proclamation--beyond any self-mastery (whether mastery over a stable or an unstable linguistic order). The content is not a what but a free who: linguistic operation has its goal and meaning outside of itself. Barth sets up no analogy of being whereby we can discern (and hence regain control of) this linguistic transcendence (169, 173). The presence of God within our words has no basis in these words but only in God’s freedom to be with us (through the Spirit, 181). Therefore, the linguistic practice of the Church (it’s “grammar”) is an exercise in humility, weakness, and dependence: without any guarantee that our words will actually become proclamation of the Word, we continue to speak our secular words, confident that God’s grace and forgiveness in Jesus will redeem our words, since God has already brought all words inside of God’s Word, Jesus Christ. Far from leading us to disparage our creaturely words, we can find new delight and pleasure in them, knowing that God is free to be with us (speak to us) in any word, and knowing that God only comes to us in the poverty of our own speech.

Saturday, July 18, 2009

Bonhoeffer and the Relative Importance of Life Together

I recently had a conversation with our priest about small groups in our church. During the meeting, I made a brief remark that Bonhoeffer, in _Life Together_, begins his description of communal life by discounting the value of it. I decided I should write out what I meant. What follows is taken from a longer paper I wrote yesterday. After the section posted here, the paper turns to "Life Together and Small Group Structures" to defend the value of small group multiplication as a way to remind ourselves that our communities are not ends in themselves but means for Christ to encounter (and means submitted to his work for his glory). I should also note that I haven't really edited the paper. But it's been over a month since my last post, so I thought I should add something.

Bonhoeffer begins his little book on Christian community, Life Together, with an attack on, of all things, the celebration of communal life. After announcing his intention to examine “our life together under the Word,” Bonhoeffer states, “It is not simply to be taken for granted that the Christian has the privilege of living among other Christians. Jesus Christ lived in the midst of his enemies” (17). He then quotes Luther, who more provocatively asserts, “The Kingdom is to be in the midst of your enemies. And he who will not suffer this does not want to be of the Kingdom of Christ; he wants to be among friends, to sit among roses and lilies, not with the bad people but the devout people. O you blasphemers and betrayers of Christ! If Christ had done what you are doing who would ever have been spared” (17-18). The Church does not exist to stay together, to cling to its own kind. On the contrary, Christians are called to “dwell in far countries among the unbelievers” (18). Christian life, even life together, is life under the Word, which means life submitted to Christ, the one who obediently went into the “far country” (Barth) to dwell with those who were not like him but were instead rebellious sinners.

Bonhoeffer’s subordination of community to Christ corrects an overemphasis on community. Christian community can only be praised after it has been devalued. Community is not our mission. It is not essential but a privilege, a gracious gift (18), and one which not all Christians have (or have continually). It is subordinated to Christ, the one who died alone (17), in the far country, for the sake of us sinners. Its value, therefore, never rests in itself but only in the one it worships, Jesus Christ. Finally, Christian community is composed of sinners (23), and therefore it is a community that can never be placed in opposition to (or closed off from) “the sinful world.” The community that shuts out the unbeliever or the stranger, the weak or the useless, may actually shut out Christ (see p. 38). To isolate the community from the world--or to place the church in opposition to the world, which amounts to the same thing--undercuts our mission, ignores our present existence as sinners justified only by grace, and risks shutting out the source of all grace, Jesus, the righteous one who dwells with sinners. All of these conclusions follow from the words of Luther placed by Bonhoeffer in the second paragraph. Life Together begins, therefore, with the stark but realistic (and necessary) reminder that our communal life is, strictly speaking, only a means and never the end, and hence, only of value insofar as it points us to our end, Jesus Christ.

This denial of the inherent value of community does not lead Bonhoeffer to assert the superiority of individual life--the book after all, is still about community. Bonhoeffer refuses to make any form--whether communal or individual, or some blend of the two--essential for Christian life. There is no right way because every step, every supposed path, exists only under the lordship of Christ. All attempts to find the right form miss Bonhoeffer’s main point: no form can guarantee that Christ is present, and therefore, all forms must be continually questioned and continually brought back into submission to Christ.

By placing communal life in service to Christ, Bonhoeffer forces us to allow Jesus to stand between us and every relationship: “we belong to one another only through and in Jesus Christ” (21). All relationships have the meaning in fulfillment insofar as they point us to Christ; therefore, Christ is at the center of all relationships. As the center, Jesus Christ stands between me and my neighbor, me and my enemy, me and my friend, me and my lover. Christ even stands between myself and me. As Augustine famously puts it, Christ “is closer to me than I am to myself.” No relationship escapes Christ’s mediation, and any relationship that tries to bypass Christ’s mediation is a sinful one. We belong to one another only through and in Jesus Christ. Only through Jesus. We can never belong to each other directly.

Jesus’ position as mediator between myself and all others destroys any attempt of heroic individualism. To assert that one can go it alone--just me and Jesus--is often an arrogant denial of Christ’s presence in and through others. We think we are strong enough, smart enough, holy enough to sustain our lives with Christ alone. But we can never be certain of our own resources; we never can rely on our strength. The one on whom we rely, Jesus, has told us where he is to be found: in our neighbor. God “has willed that we should seek and find His living Word in the witness of a brother, in the mouth of a man” (23). Jesus tells us to rely on the words of our brothers and sisters, and therefore, as people dependent on Jesus, we obey. We seek Jesus in community. We trust that Jesus will speak through the mouths and lives of those around us.

Nevertheless, we do not seek others to fill our needs, we seek Jesus in and through others. Communal life often functions as an extension of individualism. To return to the introduction, individualism is just a certain form of communal life (and hence a communal form that cannot be ended by advocating people join a community). Aware that we are finite, limited, weak, and insecure, we seek to draw others into our own “sphere of power” (33). We seek to sustain our lives--our individual, self-possessed lives--through others. Community functions as “human absorption” (ibid). Here “one soul operates directly upon another soul” (ibid). No longer does Jesus meet us through the other--and hence place himself between us and another. The other person directly satisfies our needs. They are attached to us, as extensions of ourselves, as members of our body (the original definition of a slave). We function through them; they sustain us.

This direct contact often takes the form of love but it is in fact simply the other side of domination. The other cannot be released because the other serves my needs. I need them, and that need determines our interaction. The other person is simply an extension of my own body, my own life. Love as direct contact--what Bonhoeffer calls “human love” (34)--is the desire for a community of slaves; it is the desire for a community to serve me. Whether this desire is expressed directly (“oppression”) or more subtly and coercively (“love”), the result is the same: the other person is brought under my control so as to serve and meet my needs.

Christ, as the mediator of all relationships, destroys any hope of “direct contact,” and therefore undermines all coercive relationships and communal forms. Since Christ stands between me and every other person, I “must release the other person from every attempt of mine to regulate, coerce, and dominate him [or her] with my love” (36). For Christ’s sake, we release the ones we love. We do not hold onto them, as if they were tools for the satisfaction of our own desires. We see other people as what they truly are--persons for whom Christ died. We see them as they already are “in Christ’s eyes” (ibid). This means that we lose the ability to judge others, for they are ones judged by Christ. We are willing to let go of others--to not try to influence them, but merely to “meet [them] with the clear Word of God” and let them be “alone with this Word for a long time” (ibid). Knowing that it is only through Christ that my needs are met in another person, we are free to let go of that person (or that group of people), trusting that the same Christ will continue to satisfy our desires. Forgoing all attempts at direct contact, we place our faith not in the relationship with the person but in the one who mediates--and hence controls and orders--that relationship. The relationship is never “an end itself” (35); it exists in order to serve Jesus Christ.

In Jesus Christ, all our relationships are eternally secure, for we know that we will be with our Christian community through all eternity (25). We are free to let go of our community because we trust that Christ holds all things together, and therefore, in and through Christ, we are still united to those we love. Knowing that we do not live by the experience of community but only through Christ (39), we are free to love each other truthfully, to honor one another’s freedom, and to sacrificial serve those in, and those outside of, our present community.

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Witnessing: Barth, Cixous, and the Art of Writing

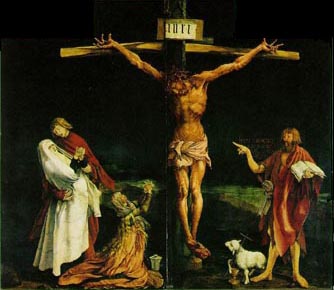

"Witnessing means pointing in a specific direction beyond the self and on to another. Witnessing is thus service to this other in which the witness vouches for the truth of the other, the service which consists in referring to this other...Standing in this service, the biblical witnesses point beyond themselves...One might recall John the Baptist in Grunewald's Crucifixion, especially his prodigious index finger. Could anyone point away from himself more impressively and completely ('he must increase, but I must decrease')...This is what the Fourth Evangelist wanted to say about this John, and therefore about another John, and therefore quite unmistakably about every 'John.'" Karl Barth, CD I.1.4.3, 109-110 [112].

So much to say about this painting--but we are only following one path here, the path to which Barth points us, the path of pointing away. Follow the prodigious finger.

To go ahead and say it: the phallic finger. Prodigious--extraordinary in size, abnormal, a miracle perhaps. Or a monstrosity. Perhaps all--that prodigious finger is not an end in itself. What it is--abnormal, excessive, monster, miracle--comes not from within, but from without. From where it points. Or, to whom. But Barth is right: it is a prodigious finger/phallus.

The object of desire, the one to whom the finger points: the monstrosity of (as) Christ. The prodigy, prodigium, Latin for monster. Or omen. Christ, the prodigy, the monstrous omen. "The prodigy is not only prewarning, but activation of the calamity at hand" (__Greek and Indo-European Etymology in Action: Proto-Indo-European *aǵ-__, Raimo Anttila, 114). The prodigious finger pointing away, pointing to the prodigy, the calamity at hand, the death of Christ.

Here we enter into the undoing. The phallic finger does not inscribe itself. It is not the goal, or object of attention. It exists in the painting as a sign, as a witness, as something to move past. It is magnified, enlarged, made prodigious so as to draw attention to its shrinking. Above the finger, it is written: he must increase but I must decrease. Enlarged, to draw attention to its shrinking. To his shrinking. To he shrinking.

Let us turn from shrinking and look at the large--and grotesque--feet of Christ. With the nail through the center, and blood dripping off the individual toes. The feet must have died first. They look ashen; even more than the rest of the dead, diseased, broken, bloody body. (I remember stories, in the Bible, about covering feet, and laying at the feet, and recall: a euphemism). Prodigious, dead feet.

Jesus' hands are also unusual. His fingers point--not to another person in the painting, but to the one absent, God, above. If there were time--I'm trying not to ramble...--we could examine those hands. One other person imitates those splayed fingers--Mary Magdalene, the smallest figure in the painting. Also, the only other one (besides Jesus) who isn't standing on her feet. The prodigious finger, pointing away from itself, towards the one with opened, uncontrolled, grasping hands. And thoroughly dead feet. (He came in the likeness of sinful flesh...).

"Writing is a passageway, the entrance, the exit, the dwelling place of the other in me--the other that I am and am not, that I don't know how to be, but that I feel passing, that makes me live--that tears me apart, disturbs me, changes me, who?--a feminine one, a masculine one, some?--several, some unknown, which is indeed what gives me the desire to know and from which all life soars. This peopling gives neither rest nor security, always disturbs the relationship to "reality," produces an uncertainty that gets in the way of the subject's socialization. It is distressing, it wears you out; and for men, this permeability, this nonexclusion is a threat, something intolerable" (Cixous, Sorties, in __The Newly Born Woman__, 86).

The permeability, the vulnerability, speaks of the end of self-mastery. Christ is the end of self-mastery. The death of human autonomy (self-government); the shriveling up of the enlarged...feet. For men, this is a threat. He must increase, I must decrease. The object of desire--the one to whom John's prodigious finger points--the crucified Christ. The death of the "phallogocentric" economy. Desired. Desirable. Lovely and teeming with life.

Cixous emphasizes writing; she performs a new writing, one not intoxicated by the desire to contain, conquer, control. Free from self-mastery, which involves (by necessity) an opposition to others: I, not you, am master. Beyond mastery, a different space, another way to write, another way to live, another way to relate. She thinks she's merely dreaming.

"Without the ambivalence, the liability to misunderstanding and the vulnerability with which [preaching] takes place, with which it is itself one event among many others, it could not be real proclamation" (Barth, 91 [94]). God speaks--the event of God's Word occurs--not in spite of, but through the weakness of our proclamation. To be a witness is to be weak. To be a witness is to have one's whole life amount to the task of pointing away, of highlighting not the self, but another. Not any other, either. But the Wholly Other--the Weakest Other, God in flesh.

Barth sometimes downplay the importance of the human form, the style of the presentation ("dogmatics does not seek to give a positive, stimulating and edifying presentation," p. 80 [82]). But he fundamentally recognizes its importance. The form does not guarantee that God speaks. God speaks always out of God's freedom. Nevertheless, one can point to Christ in a way that actually points to oneself (the kingdom of the Selfsame, in Cixous' terms). One can witness to one's strength; which means one can point away from Christ, and thus, even in the form of witnessing, one can fail to witness at all. The form matters. The way we write matters. It displays who we think we are, and, by God's grace, the one to whom we point.

To write in a way that embraces the dead, prodigious, monstrous, saving omen of Christ. And his dead feet. A challenge. Joyful, exhilarating, and terrifying. "For men, this permeability, this nonexclusion is a threat." The threat of losing control. "She lets the other tongue of a thousand tongues speak--the tongue, sound without barrier or death" (Sorties, 88). A beautiful picture of the feast we celebrated two weeks ago--Pentecost. Life beyond the dead feet. Come, Holy Spirit.